As the sun began to drop behind the westward Himalayan peaks beyond Jiwala Village, grand shapes of cascaded negative light grew in depth and intensity across the mountain range before me. What had moments before been a landscape fully lit under the direct intensity of the Indian sun now began to reshape and restructure the valley’s perceptual forms with an evolving organic magnificence. The visual spectacle unfolding before me became further enhanced with the addition of the auditory ambience of singing birds and cattle bells vibrating through the thin, high-altitude air.

Isolated for centuries from civilisation until just a few years ago, I had travelled to the mountainous Jiwala Village to witness, observe, and document the life of its inhabitants. And that night, after spending some time with the contrasting warmth of a campfire against the cool mountain air, star gazing at the Milky Way and passing satellites, I crept into my tent, eagerly anticipating the flowing day’s exploration.

Table of Contents

- The Jiwala Village Early Risers

- A Spicy Reception at Jiwala Village

- Radhe’s Arrival

- Too Much, Too Little at Jiwala Village

- A Beautiful Water Fuel

- Jiwala Village 2.0

- Hindu Creek Cribs

- Indian Unhappy Meal: Parasite Platter

- Higher and Higher

- What You Could’ve Won

- Are You Local?

- Looking Back in Time

- The Look

- Fresh Air and Perspectives

- The Boys & Girls of Jiwala Village

- P.C Pooch of Jiwala Village

- Winding Down

- Indian Hiking Beyond Jiwala Village

- Conclusion

The Jiwala Village Early Risers

Time moves differently in the mountains. At 9,000 ft, there is no such thing as a 9-5. This, one of mans only recently invented conceptions is instead replaced with the old format of life that conforms to the changing seasons. This difference means the day starts with the sunrise, whatever hour that may be and ends soon after its disappearance. Eager to utilise the blue hour for my photographs, I had set my alarm for 5 a.m. But, by the time I had mustered the motivation to exit from my warm sleeping bag and venture into the chilling elevated atmosphere, the distant echoes of locals communicating with one another had already begun reverberating as they commenced their daily chores.

From my observations, the children and women were the first to engage in their responsibilities. I witnessed the younglings gather water and wood, most likely for their mothers to prepare their father’s morning chai tea, and groups carrying large hay bails on their backs secured with a piece of fabric supported by their foreheads—food for the cattle, and, next to farming, the main lifeline of this community. However, I did observe one man with his wife and daughter ploughing a fresh lot within the cobbled walls of their property.

Nevertheless, despite a seemingly slow start to the day, once the sun passed the eastern summits and dispersed its separate energy across its plains, the village soon followed with an energy to match. Men, women and children now actively engaged in all forms of essential labour. From dusting off rugs covered in soot from the previous night’s fire to farming their crops, all stations were now occupied, including the Shisha station, manned by two gentlemen taking a more laid-back approach to the start of their day.

A Spicy Reception at Jiwala Village

Despite Google listing the location a tourist attraction, and with several commercial guide companies offering visits to the destination, the inhabitants of this village are not yet fully accustomed to visitors on their land. Especially camera-wielding Caucasians asking them to pose for portraits. Many had a firm aversion to my requests or seemed too bewildered to understand what was happening. So, after circling the location a few times for photographs and notes that morning, I sensed it was time to stop. I did not want to overdo it on the first outing. Sometimes, these things take time.

However, one of the locals did invite me for a chai tea at their home. The small rectangular building I sat outside of while sipping the warm, spiced beverage was about as simple as a house can be. It consisted of brick walls painted white with a corrugated iron roof. It was no larger than 20 square feet, about the size of a typical western garage. Enough to comfortably accommodate the family of 6, including Kishan Singh (the man that had proposed the invitation) and his wife. To whom he had married at 20 and she 16, and their four children.

Another peculiar feature of the home was the lack of a chimney. Despite a fire lit inside the house, the only means of ventilation was the front door to the home. Moreover, this was the only light source for the interior, as no windows were present in any of its four walls.

Radhe’s Arrival

Not long after my arrival, Radhe, a 37 year-old Indian national from Rishikesh who was acting as the groups guide, silhouetted at the crest of the steep bank adjacent to the building. He descended to the building and began using the outside tap to wash himself and his clothes. His casual use of the home’s amenities and calm interaction with the owner made sense after discovering he would be our sherpa. It also eluded me as to why I was there drinking chai in the first place. Because, without the status of a customer, I’m not sure I would’ve received the same hospitality at another property.

Soon after I had finished my tea and Radhe had freshened up for the day, we arranged with Kishan, for him to collect his donkey and meet us at the campsite we had erected in a patch of sheltered dead ground a few hundred meters from the rest of the residencies. So we proceeded to walk back through the herds of cattle and children now dressed in blue and white uniforms on their way to school further down the mountain to disassemble and prepare for the day’s hike.

Too Much, Too Little at Jiwala Village

For those who have not experienced India, becoming used to its customs is as demanding as a cardiovascular system adjusting to a mountain’s altitude. What I mean by this is nothing, and I mean nothing, happens fast or efficiently. What would in Western countries take a few minutes of rational discussion to draw logical conclusions can take hours here. As myself, Radhe, Bhageerth (another Indian national) and Alfie, a 33-year-old British man also with us, would experience when Kishan arrived and attempted to persuade us we needed two donkeys to transport our goods up the mountain.

In his defence, we had a ridiculous amount of gear for three days of camping. I firmly believe in carrying your gear and only packing what you need for any casual expedition like this. However, the group I had arrived with did not share this value, meaning a donkey was necessary. Moreover, as I have noted in my expanded observations of India, those of the higher castes of society have a high aversion to exertion. The act of perspiration instead left to those of the lower and easily exploited castes.

This inspection perfectly illustrated itself by the actions of Radhe and Bhageerth. As both men would only willingly carry as much as a sleeping bag each. And, to avoid breaking a sweat, negotiate the price of 1500 rupees (£15) for an entire day of the man’s service to ferry our dead weight, including a night spent with us and another 1500 for the descent the following day.

A Beautiful Water Fuel

Having waited patiently for what seemed like an eternity, Radhe resolved things with Kishan, the bags were loaded on the donkey, and we were finally off. The walk took us along a well-worn trail on the side of the mountain, trodden over centuries by the locals as they passed between their residencies we were leaving behind and their more rudimentary dwellings located further up the valley.

The first distinguishable feature passed was a small waterfall and a well-needed source of hydration. After the freshwater I bought from Budakadah (the last town in the valley) turned out to be the only drinkable liquid anyone in the group packed for the journey into the mountain. And, after a thirsty morning without properly hydrating, our dry mouths eagerly lapped the sediment-filled H2O.

Now, fully energised with bellies full of the essential substance, we continued sluggishly up the undulating terrain. That was until one of the sleeping bags strapped to the donkey somehow managed to dislodge itself and roll down the side of the mountain. Fortunately, it was wooded, and the two small boys that had accompanied us, one of whom was Kishan’s son, raced down after it. And after half an hour or so, the kit was again in our possession. At this point, if it were not for the beauty of our surroundings to distract me, my patience with the group may have begun wearing thin.

Jiwala Village 2.0

After another hour of walking in the tranquil scenery of the outer regions of the Himalayas, I noticed something unnatural emerge through the scenery. A bright, lowly saturated yellow thatching on what appeared to be a roof was distinguishable amidst the contrasting green ruff. We had arrived at the second village.

As I eagerly quickened my pace, excited to explore this new, crude mountain suburb, many more of the same thatched roofs etched into the side of the mountain began to highlight themselves. However, much to my dismay, due to the time of year, I discovered the entire place was uninhabited. Devastating, as to have witnessed life among these crude abodes constructed from slate and hay would’ve been a spectacle to behold. However, I did manage to get a tour of Kishan’s house once we had unloaded the gear from our donkey and set up camp.

Hindu Creek Cribs

As we approached what looked like nothing more than a livestock stable, Kishan opened the property’s crude gate by pulling aside a few weakly tied-together sticks and gesturing to invite me inside. Accompanying me was Bhageerth to act as a translator. We then passed several piles of hardened cow dung and ducked under the building’s low roof to enter a small space on the building’s left-hand side, where Krishnan sat on top of a rock used as a fire guard.

“This is where the goats sleep”, he said, pointing to a small rectangular area at the rear left-hand side. “And here is where we keep the cattle.”, directing my attention to the larger area to the right, which took up roughly 75% of the building’s internal space. “And where do you and your family sleep?” I questioned. “just here, next to the goats and fireplace”, he responded.

As surprising as this information was, after all, to hear about a family of 6 sleeping with goats and cows is worlds apart from anything I can imagine through my Western lens. What made the fact even more difficult to digest was when I discovered that one of these houses (not accounting for the collection and labour involved in shaping the tone) takes only four days to build. So, the effort involved in building a separate stable for the livestock would be worth it to not sleep among the filth discredited by their animals. Well, that’s what I thought. But Kishan seemed adamantly happy about the situation. So, I questioned it no further.

Indian Unhappy Meal: Parasite Platter

The following night was a rough one. Pleasant dreams of the previous day’s saga were slowly distilling in my subconscious when, at one o’clock, my mind became abruptly torn from the warmth of its subliminal blanket into a body undergoing some of the worst abdominal pain experienced in India to date. And trust me, having already endured two months of parasites, among other ailments, it was not a pleasant reality to wake to.

Writhing in agony for the following two hours, the sharp pains in my abdomen continued to increase in intensity until, at around three o’clock, my body finally gave in. And like a bolt of lightning, I was outside the tent, evacuating every ounce of body fluid. The lesson here? Eating in India is like playing Russian roulette. You can never know what or when it will get you. But eat here enough, and it’s only a matter of time before you go down with something. But if possible, stay away from the meat. Fortunately, no one else in the camp got sick.

Higher and Higher

With no alarm set the following morning, I allowed my body to recover as much as possible. That was until visiting the nearest bush could no longer be postponed. Fortunately, the weather was overcast, meaning there would’ve been no opportunity to exploit blue hour. So I didn’t feel like I had lost out on much.

After taking care of the morning’s necessary business, I greeted the gang, already awake and preparing a breakfast of instant noodles, to discuss the plan for the day. Discovering that we would no longer continue towards the summit as planned. And that, for the rest of the day, we would remain in situ. The group instead would continue to get higher by other means.

Automatic Ad Middle Of Content

What You Could’ve Won

To this point, I had been somewhat psychologically lenient with the men who had led me into the mountains with promises of documenting hash and opium producers (What this story should’ve been) and the opportunity to reach a peak to absorb the awesomeness of the Himalayas. The former a promise by Alfie, and the second from Radhe. Alfie had lost me the day before when it became apparent there would be no documentary, but now the Indians had lost me also. I now felt alone on the mountain.

And, while the journey was still rewarding, it was thoroughly enjoyable to have rest from country overcrowded cities. The situation was a tune to promises of a car for your birthday but instead receiving socks. The latter is still handy, yet the former would’ve been far more exciting and advantageous. Nevertheless, determined to make the most of the situation, I decided to trek to the village solo, not to lose the opportunity to document the villagers further.

Are You Local?

had grown up, worked and weathered under such strenuous, challenging and often dangerous situations as those involved in high altitude mountain life. That is why I was not surprised with how the village responded to my visit. On my first approach the day before, the villagers had perhaps allowed me to get close out of confusion. However, now they understood who I was, and, without the presence of the Indian guides, the attitude shifted from a hesitant cautiousness to full-fledged anxiety and disapproval.

This energy shift first presented itself when approaching an elderly couple tending to their cows. To begin, I believed things would go well. That was after giving a friendly wave to the people and receiving what I thought to be one back. However, the Western wave is not an understood signal in the Indian mountains, so it was most likely a mirroring response based on anxiety.

Fortunately, I had some cigarettes with me and exchanged one for the man’s short, divided attention. But, the wife was entirely uninterested and, although she seemed happy to pose the previous day, vacated the area sharpish, along with her flock of grazing cattle and the storytelling content from the frame. After getting away with what seemed like a cheeky few shots, the man had enough and began gesturing me away with his hand like you would a fly.

The response was much the same from the villagers throughout the rest of the day. So, Because I was having such bad luck and the weather was not ideal for undirected outdoor portraiture, I decided to take a small hike along a different route on the opposite side of the mountain instead.

Looking Back in Time

Despite gaining no access to the villagers’ homes nor the inhabitant’s willing participation in my photography, it was still possible to witness, sit with and appreciate the wonder of the alien world I was experiencing. It was as if the jeep that had driven us up the meandrous mountain path had, by doing so, unlocked some temporal code transporting us back in time to a period before touchscreens, computers and the internet. And before the secret of winged travel, harnessing the power of steam or even canals to transport goods. Before me, I witnessed a world that had remained fundamentally untouched and unchanged since the beginning of the agricultural revolution some 12,000 years ago.

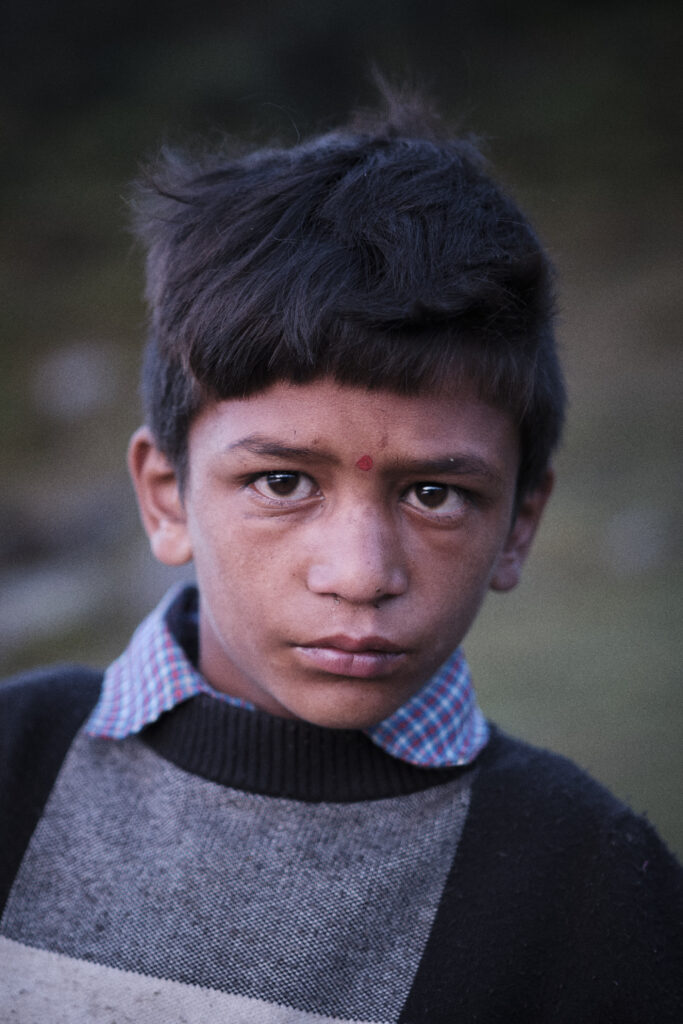

The Look

Yes, some here had smartphones and clothes made in factories. However, at its core, it was essentially authentic to how humans lived before the advent of time stamping, the division of labour, and the absurdity of the necktie, when people’s concerns were on completing crop cycles instead of Netflix series. A time When teeth were free from cavities and dentists an uncommon necessity. And when family and community ties were tougher than diamonds.

And this raw, bare-boned existence was not only evident in the way the people here moved. Because, as I came face to face with the community members, there was something within their gaze, behind the piercing coarseness of each dilated sphere, that exemplified a palpable connection to a legitimate perception even the self-proclaimed spiritual babas of India’s modern civilisation could not tune into. This feeling was especially the case for the older and younger members, who were either too old or too innocent to be interested or exposed to the outside world. As in each fractional instance, within the abyss of their nebulous pupils, it was as if I were staring into the eyes of God itself.

Fresh Air and Perspectives

Having decided to explore beyond the opposite side of the hamlet, and after trekking higher onto the mountain, I found myself atop the ridge of the Jiwala village, staring down a horizon filled with multiple peaks as far along the visible curvature of the earth I could see. I took a deep breath and exhaled slowly. So this is what freedom feels like, I thought to myself.

It can be easy to be drawn into believing that the lives we live under our state’s modern pretence of freedom are, in fact, in line with its true nature. However, it is crucial to remember the notion is nothing more than an abstraction. And only when confronted with a scale of such things as the humbling majesty of a mountain range can a perspective of modern existence point to alternative conclusions.

It is as if the further down to sea level one becomes, along with increasing proximity to urbanised spaces, our true nature begins to shed from us like the dying leaves from an autumn branch, lost as we compartmentalise our physical and psychological spaces into increasingly shrinking chunks of reality, reducing the pressure on our fragile human minds.

Unfortunately, the perspectives of modern man have diminished so considerably that they exist almost entirely in the spaces between our noses and the algorithmically tailored content presenting itself within the bezels of our smart devices. Even for those who manage to break their gaze within our utopias of tribal capitalism and look towards the sky, nothing but an ambient haze of light pollution is visible. A relic of our forefather’s ingenuity. And a lasting legacy of our fight for dominion over reality and separation from divinity.

The Boys & Girls of Jiwala Village

Having spent an extended time sitting and thinking on the ridge, I noticed the sun was starting to hang low in the sky. It was time to leave and head back to the camp that was now perhaps ten kilometres away. Because I was also not innocent of entering the mountain without due preparation. And I did not fancy navigating my way there with my smartphone’s torch.

On my return, I noticed a greater volume echoing among the crude squares nested into the sides of the mountains. The children were out of school and were now engaging in something as uncommon to observe in England as the gigantic eagles which circled overheard here in their abundance, actual physical play.

It was also interesting to note the difference my presence made to the boys and girls there. In the case of the former, the boys were much more self-confident and curious to engage with me. Specifically, if the group they were with grew beyond three or four. There was still an air of caution. However, calling me or approaching to examine my camera was not uncommon for them. Alternatively, the girls would act with utmost reservation in my presence. As would many of the women. But as the number of females going missing reaches the hundreds of thousands every year in India, It was an unsurprising reaction.

P.C Pooch of Jiwala Village

In the mountains, there are no public services to protect or serve the people. The closest police station or hospital is in Budhkedar, located several kilometres down the mountain. This fact means they are self-reliant and settle disputes as part of a community among themselves, as they have done for a thousand years. For instance, for a mild misdemeanour committed by one of the community, a punishment like restricted access to specific water stations may be given (However police involvement for more severe cases is required).

However, the best policy is always to put in place preventative measures. And a popular one here, as is true for most developing nations, is the use of dogs. Not only acting as incredible alarm systems, the kay-nines are often ready to attack and die for their owners. I would discover after approaching a family of 9 huddled together on top of a hill, all surrounding the father, watching the screen of his smartphone.

As I approached them with camera in hand, their black shaggy mutt was between us from nowhere, barking ferociously with eyes that said if you come any closer, you’re a goner. What a terrible shame, as it could’ve been the money shot of the entire expedition. But you can’t have them all.

Winding Down

The following morning, the group lethargically packed the camp, and we returned once more to where we had been the previous day. Alfie Rhaday and Bhageerth decided to leave to discuss other business with the villagers there, and I was left alone.

During this time, a few local children decided to take a keener interest in me than before. Starting from around 400 meters, a boy and girl began to approach gradually until, at 50 meters, I managed to persuade them to join me to roam freely in the campsite I had constructed. The girl was, of course, hesitant and shy. However, the boy was eager for the opportunity. And over the next several hours, we grew comfortable in each other’s presence. He even convinced a group of girls circling the site to get close enough for a photograph, A fun game of cat and mouse that lasted several hours. And I let him play with and explore my camera.

The rest of the gang soon returned, and we spent the remainder of the night huddled around a campfire, appreciating the spectacular views of the star-filled sky provided by the high altitude, tin air and low light pollution. Letting the day’s previous sensory experiences digest and consciously acknowledge the final moments of peace before beginning our descent and reintegrating into civilisation the ensuing day.

Indian Hiking Beyond Jiwala Village

For those interested in taking genuine hikes through the mountains of the Indian Himalayas, I can’t, with integrity, recommend you do so. Not only based on this experience, which was more of a casual trip to the mountains, and so somewhat excusable. But because of how Indians generally approach communication, their ability to organise thoroughly, and a fear that if something were to go wrong at altitude, you would not be in good hands. These observations are confirmed by others, including those who have paid to take several day hikes in the mountains.

If you have an unlimited amount of time and money, then by all means, explore these ranges, especially if you are interested in witnessing the Indian-specific culture which exists here. However, for those with more restrictive timeframes and a greater expectation from your service providers, you are better off exploring alternative options such as Nepal.

Conclusion

Overall, despite the many quarrels, inefficiencies of the team, poor communication, my V&D, lack of fresh water, not reaching the summit, poor reception from the villagers, and not getting the story I had primarily come for, the trip to the Jiwala Village was worthwhile. In many instances, I had to stop and remind myself to be more present in the moment and appreciate simply being. For me, it is what the trip evolved into and was my greatest takeaway.

It was also my first time coming face to face with a way of mountain life I had not previously experienced as it was a perfect exercise for things to come for my upcoming visit to Nepal. Jiwala village story image, Jiwala village story image, Jiwala village story image, Jiwala village story image, Jiwala village story image.